Arda Yurtçu Exposition Project

- Arda Yurtcu

- Aug 10, 2023

- 4 min read

Si je devais créer ma propre exposition dans un monde hypothétique, je commencerais par cette merveilleuse œuvre d'Édouard Manet. Voici un projet d'exposition sur lequel j'ai travaillé l'année dernière.

Tous les peintres de cette exposition ont vécu à Paris et à Istanbul. Jean-Léon Gérôme et Édouard Manet sont des Parisiens, Osman Hamdi Bey est un peintre turc (1842 - 1910) qui a fait ses études à Paris. Hamdi Bey a été l'élève de Gérôme, l'influence stylistique est évidente.

L'une des idées principales de l'exposition est que l'accusation portée contre les orientalistes français de représenter des scènes d'Orient simplifiées n'est pas fondée. La représentation du monde islamique par les orientalistes français était souvent plus naturaliste.

ParISTanbul: Representation of the Other in Modern Art

Édouard Manet to Osman Hamdi Bey

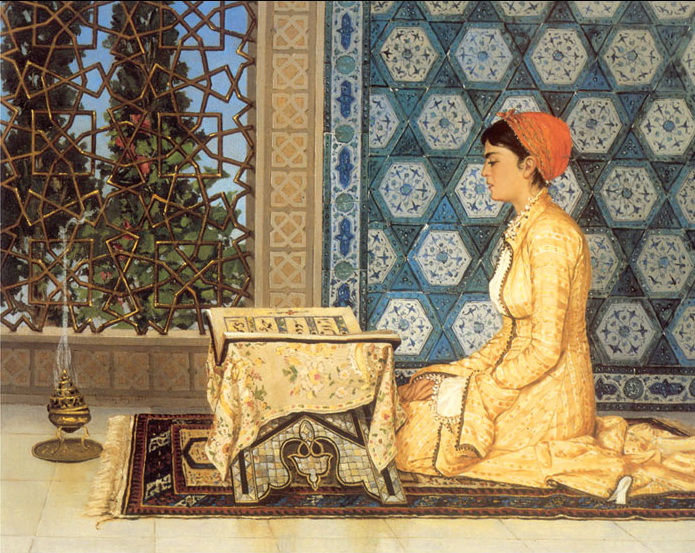

Artists have always been passionate about portraying the cultures and social milieus that they perceived as distant from their own. Until the 19th century, the Europeans had minimal contact with the cultures in the Middle East. Art history narratives that were displayed in museums frequently degraded French Orientalists for their opulent eroticism of harem scenes. In the Orient– especially the cultural hubs such as Istanbul, Egypt– the late nineteenth century was an era of significant artistic transformation in Islamic art. Osman Hamdi Bey was a pioneering Ottoman intellectual who grew up during the innovative Tanzimat era. He was not only a prominent painter of religious art but also a major actor in the process of Westernization.

Featuring nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Orientalist paintings by artists born in Europe and Ottoman Empire, this exhibition questions the ideological underpinnings of the narratives in the museums. Not only it explores the profound and ongoing exchange between modern European and Islamic art, but also how the art historical canon itself has been a site of tension. Throughout the 19th century, the manner in which European collections reflect the portrayal of other has been criticized by the art intelligentsia of Islamic societies. They argued that Ottoman artists of the time depicted religious settings with a view from within, whereas French artists attempted to satisfy the Oriental fantasies of Western viewers.

The exhibition invites us to question the interactions between European and Ottoman artists in the modern period. The exhibition offers a flexible lens to question whether artists ‘exoticized’ vast regions and different cultures.

Are the Orientalist Art Canons imagined by and serving a narrow art intelligentsia? How the European and Ottoman artists’ representations of the other were displayed in museums? How do modern paintings reflect certain views of gender, culture, and religion?

Édouard Manet– Olympia (1863)

Olympia –a Parisian prostitute who confidently reclines on a bed– looks at the viewer with a direct, almost confrontational gaze, as if placing the viewer in the role of her client. She wears nothing but a thin black ribbon around her neck and a gold bracelet on her wrists, symbolizing elegance and wealth. In the 19th-century French salon painting audience, women's body was traditionally associated with the nudity found in the art of antiquity. Instead of reinventing the forms and ideals in the classical past, Manet subversively came against it and portrayed what later will be considered the epitome of his modernist work. The formal qualities of Laure’s depiction, the prostitute's black maid, has often been a point of contention– the compocampsition simultenaously centers and obscurs her vis-à-vis Olympia.

Osman Hamdi Bey -- "Old Man in Front of the Graves of Children" (1903)

Known as ‘the first and last Orientalist painter’, Hamdi Bey made his name through his portrayal of centralized figures in religious settings. Standing in front of a stone-draped tombs in a ‘türbe,’ (religious architecture in Ottoman Turkish) a man stands in a position that one could interpret as a prayer gesture. The extremely realistic depiction of the niches and the exotic mosaics capture attention. The one-point perspective and emphasis on the decorative space were characteristic choices of the artist for reflecting the authentic Islamic architecture of his time. The walls of the room are filled with Islamic inscriptions that would have looked very exotic to the Western observer of the time.

The Carpet Merchant, JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME (1869)

Jean-Léon Gérôme visited Cairo and Alexandria (modern-day Egypt) from the 1850s onward, collecting textiles, photographs, and other props to use in his studio in France. Though his detailed depiction of two carpets lends this painting a very realistic appearance, Gérôme has later been criticized for its stereotypical portrayal of an Egyptian carpet vendor. The 20th-century art intelligentsia in Europe knew that the brightly costumed passersby revealed Gérôme’s desire to appeal to the European fantasies of the Arab-Islamic world. Some museums in Paris -Gérôme’s hometown- interpreted such depictions as the faithful records of an unchanging “Orient,” disregarding the romanticized and idealized view of the merchant.

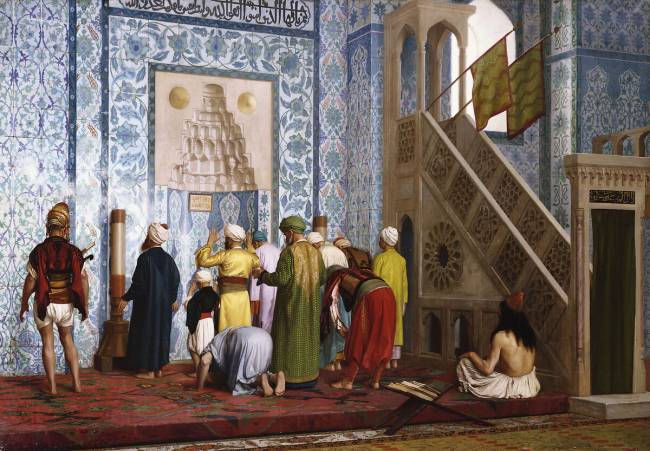

The Blue Mosque, by JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME, 1878

Though many French Orientalists’ paintings lose their credibility after a close scrutinization and have therefore been perceived as the European artist's distorted perception of the Middle East, the details of the mosque portrayed in Gérôme’s paintings suggest another narrative. Here he depicts the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Istanbul, after his visit to the Ottoman Empire in the 1880s. He demonstrated both his encyclopedic knowledge of Islam and his profound observations of some of its most distinctive cultural traditions. In the center of the composition, however, one man departs from the norm. He raises his hands, palms facing the qibla, as if to recite "Allah-o-Akbar" ("God is Great"). The light-blue geometric patterns representative of Islamic mosaics are in contrast with the colors of the praying Muslims.

Comments